Stars Around the Milky Way: Cosmic Space Invaders or Victims of Galactic Eviction?

February 26, 2018

Astronomers have investigated a small population of stars in the halo of the Milky Way Galaxy, finding its chemical composition to closely match that of the Galactic disk. This similarity provides compelling evidence that these stars have originated from within the disc, rather than from merged dwarf galaxies. The reason for this stellar migration is thought to be theoretically proposed oscillations of the Milky Way disc as a whole, induced by the tidal interaction of the Milky Way with a passing massive satellite galaxy.

If anyone from outer space would like to contact you via “space mail”, your cosmic address would include several more lines including “Earth”, “Solar System”, “Orion Spiral Arm” and “Milky Way Galaxy”. This position within our home galaxy gives us a front row seat to explore what is happening in such a galaxy.

However, our internal perspective presents some challenges in our quest to understand it - for example for outlining its shape and extent. And yet another problem is time: How can we interpret galactic evolution if our own life span (and that of our telescopes) is far less than the blink of the cosmic eye?

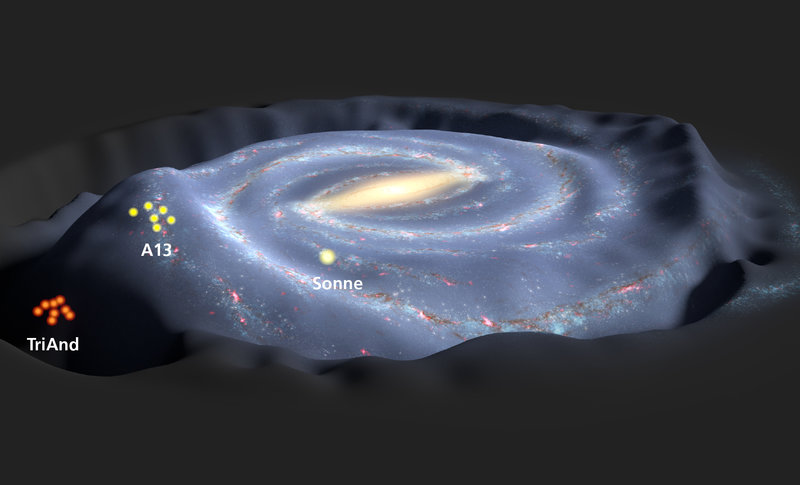

Figure 1: The Milky Way galaxy, perturbed by the tidal interaction with a dwarf galaxy, as predicted by N-body simulations. The locations of the observed stars above and below the disc, which are used to test the perturbation scenario, are indicated. © T.Mueller /NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Today, we have a fairly clear picture of the broad properties of the Milky Way and how it fits among other galaxies in the Universe. Astronomers classify it as a rather average, large spiral galaxy with the majority of its stars circling its center within a disk, and a dusting of stars beyond that orbiting in the Galactic halo.

Stellar streams and clouds in the halo

These halo stars seem not to be randomly distributed around the halo - instead many are grouped together in giant structures - immense streams and clouds of stars, some entirely encircling the Milky Way. These structures have been interpreted as signatures of the Milky Way’s tumultuous past - debris from the gravitational disruption of the many smaller galaxies that are thought to have invaded our Galaxy in the past.

Researchers have tried to learn more about this violent history of the Milky Way by looking at properties of the stars in the debris left behind - their positions and motions can give us clues of the original path of the invader, while the types of stars they contain and the chemical compositions of those stars can tell us something about what the long-dead galaxy might have looked like.

Not intruders, after all?

An international team of astronomers lead by Dr. Maria Bergemann from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg now found compelling evidence that some of these halo structures might not be leftover debris from invading galaxies but rather originate from the Milky Way’s disc itself!

The scientists investigated 14 stars located in two different structures in the Galactic halo, the Triangulum-Andromeda (Tri-And) and the A13 stellar overdensities, which lie at opposite sides of the Galactic disc plane. Earlier studies of motion of these two diffuse structures revealed that they are kinematically associated and could be related to the Monoceros Ring, a ring-like structure that twists around the Galaxy. However, the nature and origin of these two stellar structures was still not conclusively clarified. The position of the two stellar overdensities could be determined as each lying about 5 kiloparsec (14000 lightyears) above and below the Galactic plane as indicated in figure 1.

Bergemann and her team, for the first time, now presented detailed chemical abundance patterns of these stars, obtained with high-resolution spectra taken with the Keck and VLT (Very Large Telescope, ESO) telescopes. “The analysis of chemical abundances is a very powerful test, which allows, in a way similar to the DNA matching, to identify the parent population of the star. Different parent populations, such as the Milky Way disc or halo, dwarf satellite galaxies or globular clusters, are known to have radically different chemical compositions. So once we know what the stars are made of, we can immediately link them to their parent populations.”, explains Bergemann.

Tracing the origin of stars with chemistry

When comparing the chemical compositions of these stars with the ones found in other cosmic structures, the scientists were surprised to find that the chemical compositions are almost identical, both within and between these groups, and closely match the abundance patterns of the Milky Way disc stars. This provides compelling evidence that these stars most likely originate from the Galactic thin disc (the younger part of Milky Way, concentrated towards the Galactic plane) itself, rather being debris from invasive galaxies!

But how did the stars get to these extreme positions above and below the Galactic disk? Theoretical calculations of the evolution of the Milky Way Galaxy predict this to happen, with stars being relocated to large vertical distances from their place of birth in the disc plane. This “migration” of stars is theoretically explained by the oscillations of the disc as a whole. The favoured explanation for these oscillations (or waves) is the tidal interaction of the Milky Way’s Dark matter halo and its disk with a passing massive satellite galaxy.

The results published in the journal Nature by Bergemann and her colleagues now provide the clearest evidence for these oscillations of the Milky Way’s Dark disc obtained so far!

A dynamical home galaxy

These findings are very exciting, as they indicate that the Milky Way Galaxy's disk and its dynamics are significantly more complex than previously thought. “We showed that it may be fairly common for groups of stars in the disk to be relocated to more distant realms within the Milky Way—having been 'kicked out' by an invading satellite galaxy. Similar chemical patterns may also be found in other galaxies—indicating a potential galactic universality of this dynamic process.” said Allyson Shefield from LaGuardia Community College/CUNY, a co-author on the study.

As a next step, the astronomers plan to analyse the spectra of other stars both in the two overdensities, as well as stars in other stellar structures further away from the disc. They are also very keen on getting masses and ages of these stars in order to constrain the time limits when this interaction of the Milky Way and a dwarf galaxy happened.

“We anticipate that ongoing and future surveys like 4MOST and Gaia will provide unique information about chemical composition and kinematics of stars in these overdensities. The two structures we have analysed already are, in our interpretation, associated with large-scale oscillations in the disc, induced by an interaction of the Milky Way and a dwarf galaxy. Gaia may have the potential to see the connection between the two structures, showing the full oscillation pattern in the Galactic disc”, says Bergemann, who is also part of the Collaborative Research Center SFB 881 “The Milky Way System”, located at Heidelberg University.

Background information

The results described here were published in Bergemann et al.

” Two chemically similar stellar overdensities on opposite sides of the Galactic disc plane” in the journal Nature.

Information about advanced access to the Nature article can be obtained at press@nature.com

The research was performed in the framework of the Collaborative Research center SFB 881 (Heidelberg University) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation).

The MPIA researchers involved were Maria Bergemann, Branimir Sesar and Andrew Gould in collaboration with Judith G. Cohen (California Institute of Technology), Aldo M. Serenelli (Institute of Space Sciences/IEEC-CSIC), Allyson Sheffield (LaGuardia Community College/CUNY), Ting S. Li (Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory), Luca Casagrande (The Australian National University), Kathryn Johnston and Chervin F.P. Laporte (both Columbia University, New York), Adrian M. Price-Whelan (Princeton University) and Ralph Schönrich (University of Oxford, UK).